|

A PRIMER IN SIMCOE GEOMETRY.

We've mentioned before that city bikes tend to be regional objects. This

isn't a criticism, it just makes sense. Racing bikes meet at

international races and events. It is here that ideas are compared and

adapted and the racing bike reaches relative uniformity. From our

experience we found that there is very little uniformity between city

bike geometries, largely because no one has ever asked the

question! And, while recent attempts have been made in North

America to synthesize a uniform design principle, most results show a

clear lack of experience. Beach

cruiser geometry often becomes the fallback position, or the geometry

falls victim to monetized cost-cutting (whether that means building a

bike around the shipping box size or trying to build one-size-fits-all

frames). At Simcoe, we knew we had a chance to truly evolve the city

bike, and that's exactly what we did. Read on!

|

|

|

|

Simcoe

was first built on the face-to-face retail experience of Curbside Cycle

and the cross-continent conversations of Fourth Floor Distribution. So,

we had a pretty good sense of what was needed, we just needed someone

to design it! And so, we hired Toronto local Dave Anthony (above), who

also used to head the R&D departments of FSA and Cervelo (and owns a

little consulting company called Cyclo Mondo). It's not too often you

can find a guy who knows how to design frames and hubs and

headsets. Dave admitted Simcoe was a difficult project yet. With no

uniform principle to improve upon - which is what an engineer is usually

trying to do - we had to develop the principle ourselves. And, while

that's no easy task, we had plenty of experience to push us in the right

direction. So, here's what we did....

|

|

|

|

First,

we took the city bikes of Europe and compared their geometry. The

results were shocking. Dutch bikes still have high bottom brackets

because the bikes were originally fixed gears - and that was a century

ago! This high center of gravity was stabilized through an insanely long

wheelbase, making the bikes both unusually high and long.

English bikes seemed to correct this problem but still used 60-66 degree

seat/head angles, making climbing both difficult and sloppy.

Meanwhile, Italian city bikes had seat angles at an insane 90 degrees,

perfect for time trialling to the coffee shop. (Yikes!). Only Denmark

seemed to be producing modern geometries, but with a population of

only six million people, they lacked the economy of scale to produce

anything other than designer price-points. Clearly, we had our work cut

out for us...

|

|

|

|

Attempts

at building a North American city bike seemed even more

confused, often betraying a bias towards the (disposable)

California beach cruiser market. Some bikes had wheelbases and seat

angles that lowered the rider far below traffic and crated questionable

pedalling efficiency. Other bikes seemed to be designed around

principles totally unfamiliar - even cynical - to the bicycle industry.

In industrial design it's not uncommon to be taught that an object

should be engineered around the shipping box size. That's strange to us,

but then we also imported fully built Dutch bikes for a while (which we

admit was a little silly). In any case, you don't ride a box.

Moreover, you can't manufacture a one-size-fits-all frame (there's no

such thing) just for the sake of economy-of-scale. In short, we found

there was far too much focus on brand and far too little focus on

engineering good fit or real transportation solutions. We knew what was

wrong, now we had to make it right...

|

|

|

|

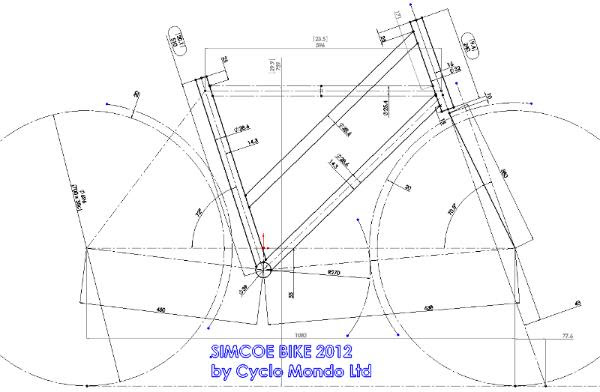

If

you look at a city it's made up of tight corners and long

straight-aways. And hills. Thus, a bike with great acceleration, snappy

handling and a longish footprint is absolutely required. A lot of early

90's mountain bikes struggled with this same question, especially those

legendary folks at Bridgestone. Our man Dave engineered

the Simcoe with a slightly shorter front-center and slightly longer

rear-center - keeping aware of toes and panniers - and a relatively

relaxed seat-tube angle combined with a slightly steeper head-tube

angle. The long and short (ha,ha) of all of this is that a Simcoe can be

a speedy longer distance commuter or agile short-burst city bike

designed to climb efficiently and, of course, carry your kids and

groceries. Simcoe isn't just good-looking - that's just the seduction.

It's meant to absolutely blow minds on test-rides.

|

|

|

|

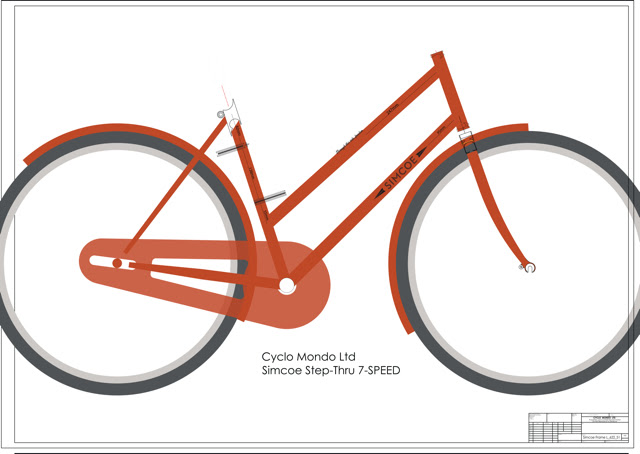

Perhaps our coup-de-grace was the step-through bike. Unlike

other companies who first launched a one-size-fits-all frame for women,

we knew that women are the major city bike consumer and take fit

seriously - like clothing. We built our 18" Simcoe with 650A wheels to

lower the center of gravity for shorter cyclists and kept a 700c for the

20" size. We also refused to build a bike with an exceptionally

long (Dutch) or short (Mixte) head-tube, opting instead for the spot in

between. This was a brilliant lesson learned from old North

American companies like Schwinn and CCM who reduced parts across models

while still achieving proper-fit. What we're

really doing is capitalizing on the timeless functionality of a quill

stem. If you really want to achieve Dutch or Mixte positions, it's just

an allen-key away.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Simcoe was borne out of honest shopkeeping and the responsibility that comes from face to face transactions. And, the luck of being in a prosperous rustbelt ciy. Toronto might be one of the strangest cities in North America, a place that built subways while NYC built expressways. It is, in many ways a city that has modelled the creative class since the 60's (not surprisingly, Richard Florida lives here and Jane Jacobs was once our customer). Simcoe grew out of Curbside Cycle. For twenty years the city cyclist - especially women - have been our primary customer. After years of replacing exposed cables and drivetrains and hearing about customers laundry costs we were the first to import Batavus and Pashley bikes. We were proving the market four years before companies like Linus even existed. We started Fourth Floor and even distributed Linus in Canada, stunned by the power of good branding but convinced we could do much, much better. Simcoe is really a story about the evolution of the city bike in North America. It's a commitment to building better lifestyles though quality and beauty.

|

|

|

|

In sum, Simcoe is about building an experience that provides longevity, exhilaration, and identity. And identity, as our discussion above has shown, is deeply important. Building identity is as much about color as it is about engineering careful attention to details. The Simcoe colors and logo were the brainchild of Markus Uran (above), owner of Metsa clothing. In an industry dominated by the California bike industry and its bright citrus colors, we wanted something that represented the industrial and autumnal colors of our home up here in the rustbelt. Post-recession America is searching for its origins, and there has been an aesthetic return to the Northeast, whether that's in heritage clothing brands like Woolrich or Penfield, or kids moving back to Detroit and roasting coffees. But color and typeface is just the invitation. Simcoe is a brand that wants you to look under the hood and fall in love with the details, whether that's the leather washers on the fluted fenders, braze-ons for dutch rear wheel lock, stainless steel eyelets on the rims, or the Pantone laces on the Brooks B68 saddle. It's all about integrity and a story that keeps unfolding years after purchase.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|